Our History

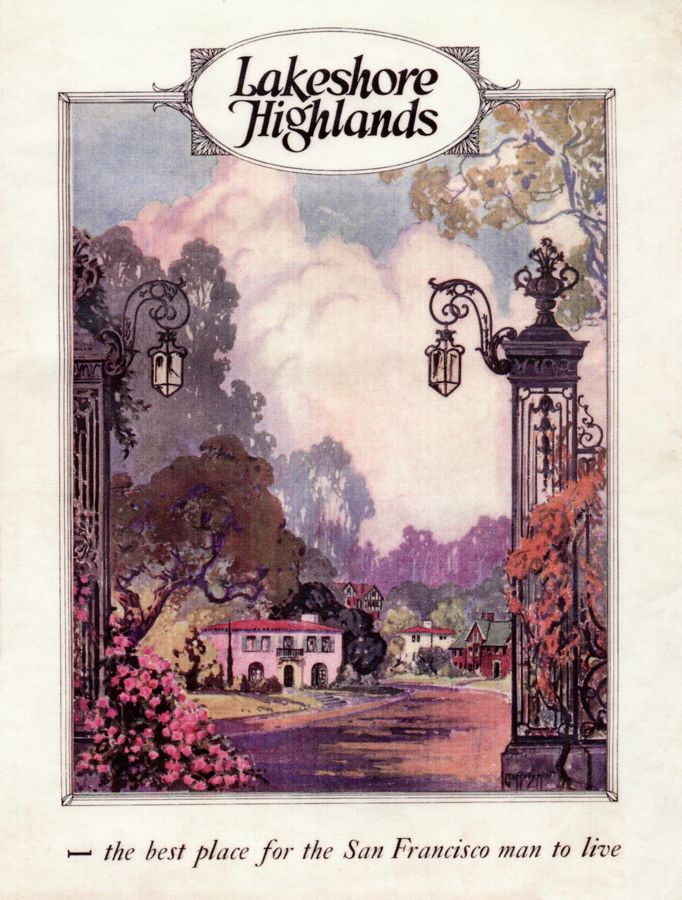

Lakeshore Highlands: Twenties Residence Park in Trestle Glen

“…a veritable fairyland of rolling hills and wooded dales right in the heart of Oakland near famous Lake Merritt and its flower filled parks-six minutes by motor, nine by car, from Oakland City Hall, and 36 minutes by the Key route from San Francisco. Nothing approaching Lakeshore Highlands in attractiveness ever has or ever will be offered to the seeker for ideal home conditions in the Bay Region … Beautiful home sites, of varying sizes, $1250 to $3000…”

“…a veritable fairyland of rolling hills and wooded dales right in the heart of Oakland near famous Lake Merritt and its flower filled parks-six minutes by motor, nine by car, from Oakland City Hall, and 36 minutes by the Key route from San Francisco. Nothing approaching Lakeshore Highlands in attractiveness ever has or ever will be offered to the seeker for ideal home conditions in the Bay Region … Beautiful home sites, of varying sizes, $1250 to $3000…”

Sound too good to be true? These were the promises of a 1922 San Francisco Social Register advertisement of the Walter H. Leimert Company, describing Lakeshore Highlands. The area, above the Lakeshore commercial district and below Crocker Highlands school, includes such picturesque streets as Rosemount, Longridge, Larkspur Lane, Hillcroft Circle, and Trestle Glen.

As remarked in another promotional article describing Leimert’s “ideal home park,” it was “a far cry from Indian teepees to stately mansions, from a stretch of tule growth to sweet rose gardens, from wilderness to paved streets, electric lights, streetcars and automobiles” (Home Designer, November 1924). Indeed it was, and there were those who regretted the passing of the old at the same time Leimert sang the praises of the new.

Once a laurel-lined area along a mossy creek running into what is now Lake Merritt, the glen was known as Indian Gulch to early Oaklanders, though the Indians were long since displaced by the Spanish. In 1820 the Spanish crown granted most of what is now Alameda County from Albany to San Leandro to a retired army sergeant named Luis Maria Peralta. What use the Peraltas made of Indian Gulch can only be surmised, but they used the entire rancho primarily for cattle raising. Later, with the discovery of gold and the emergence of the “instant city” of San Francisco, the family sold lumbering rights to redwoods in the hills. Eventually the hills were bare save for scrub oak and buckeye. As Oakland grew, and especially after the devastating drought of 1862-64 killed off the cattle herds, interest in the outlying land shifted from ranching to recreation.

An 1871 bird’s eye map labels the area that is now Trestle Glen as Lake Park, and shows roads winding over the hills and past three small lakes. In the 1880’s the area belonged to banker Peder Sather (memorialized by Sather Gate at the University of California). After his death in 1886, his wife Jane allowed the land to be used as a park.

The name Trestle Glen dates back to this period, to approximately 1893 when Francis Marion “Borax” Smith’s Oakland Traction Company extended a trolley line from downtown Oakland up Park Boulevard to Grosvenor Place. From a point just above where Holman Road crosses Grosvenor to about Underhills Road, a large wooden trestle bridge was constructed to carry the carloads of picnickers across Indian Gulch and into Sather Park. As one visitor recollected:

“In those days Trestle Glen was a long ways from the city of Oakland… on the floor of the glen at the end of the bridge a pavilion was erected and suitable outbuildings for restaurants, etc., were built nearby. Dances, conventions, camp meetings, and gatherings of various kinds kept the glen pretty well patronized during the summer months. The Salvation Army held its annual camp meeting there on several occasions at which time Trestle Glen was about the busiest, liveliest place in the East bay region… ”

The electric trolley that trundled over the bridge featured double-deck seating and brass handrails. Mark Twain is among the notables known to have made the trip.

The electric trolley that trundled over the bridge featured double-deck seating and brass handrails. Mark Twain is among the notables known to have made the trip.

Borax Smith quickly consolidated the various East Bay railway lines into the Key System, and connected it to San Francisco by way of an elaborate ferry system. In 1895 Smith joined Frank C. Havens, a real estate magnate who controlled 13,000 acres of East Bay hilltop land, to form the Realty Syndicate. At that moment, the days of leisurely picnicking and romantic strolling in Sather Park became numbered.

The Realty Syndicate acquired the Sather Estate in 1904, and by 1906 the Trestle Glen crossing was gone. In 1911 Wickham Havens, Frank’s son, filed a subdivision map for Crocker Highlands. And in 1917 the Lakeshore Highlands Company, of which Wickham Havens was president, filed a subdivision map covering the hills on either side of Trestle Glen, from Lakeshore Avenue to Grosvenor Place, in what had been known as Sather Park.

Meanwhile a movement had arisen to preserve Trestle Glen as a public park. As early as 1909, consulting New York landscape architect Charles Mulford Robinson proposed to Oakland’s newly established Park Commission a comprehensive plan for an unprecedented system of public parks for Oakland. The purchase of old estates like DeFremery and Mosswood parks was one of his proposals; another was acquisition of the privately owned land around Lake Merritt. A third proposal, not acted upon, was a greenbelt connecting the lake with a park area along Trestle Glen, up Park Boulevard, winding around the city of Piedmont, through Mountain View Cemetery, and back to Lake Merritt. In 1914 under the sympathetic administration of Mayor Frank Mott, the Park Commission actually acquired an option to purchase Trestle Glen, but was unable to arrange financing during Mott’s term. In 1915 John L. Davis, a fiscal conservative and opponent of the park project, was elected mayor, and he defeated a plan whereby the city could have purchased the land on an installment basis.

So Wickham Havens took action to create his “residential park” in Lakeshore Highlands. He retained the Olmsted Brothers (whose father, Frederick Law Olmsted, designed Mountain View Cemetery as well as New York’s Central Park) to prepare a site plan for an exclusive, restricted, upper-income residential suburb along the lines of San Francisco’s 1912 St. Francis Wood. Inspired by England’s “garden suburbs,” the Olmsteds laid out winding streets following natural contours, leaving natural areas along the creek (later Trestle Glen Road) and smaller park areas scattered throughout the tract. The monumental entrance portals to the tract were designed by Bakewell & Brown, architects of San Francisco City Hall and a number of opulent houses in Adams Point, and the sales office by the similarly eminent Louis Christian Mullgardt.

The Lakeshore Highlands Company itself built many of the houses during the tract’s first years, but later it was more common for the homeowner to buy a lot and commission his or her own house. The tract’s building restrictions required that each house cost at least $3000 more on some lots-and some owners spent as much as $50,000, an enormous sum at the time. Lakeshore Oaks too was initiated with company-built homes, ten fully decorated model homes which were shown as the California Complete Homes Exposition in the fall of 1922, and drew tens of thousands of visitors.

Most lots were filled during the halcyon days of the 1920’s, but building continued into the 1930’s and a few lots remained even  after World War II. Many of Oakland’s best known architects worked in the neighborhood over the years: Julia Morgan, Maybeck & White, Charles McCall, A.W. Smith, Hamilton Murdock, William Schirmer, Kent & Hass, Frederick Reimers, William Wurster, Irwin Johnson, and others.

after World War II. Many of Oakland’s best known architects worked in the neighborhood over the years: Julia Morgan, Maybeck & White, Charles McCall, A.W. Smith, Hamilton Murdock, William Schirmer, Kent & Hass, Frederick Reimers, William Wurster, Irwin Johnson, and others.

Shielded by private restrictions against multiple dwellings as well as by zoning, the area retains its period character up to the present day. The houses are by and large romantic and picturesque, exhibiting post-World War I taste for country charm and European culture. Italian Renaissance, Tudor, Spanish, Monterey, French provincial, and Colonial styles abound. As Walter Leimert would be the first to point out, the Lakeshore Highlands/Trestle Glen area remains one of substantial architectural interest as well as natural beauty.

Excerpted from an article by Deborah Shefler and Dean Yabuki. Reprinted courtesy of the authors and the Oakland Heritage Alliance.

Olmsted Legacy and Lakeshore Homes

Beginning in 1857 with the design for New York City’s Central Park, Frederick Law Olmsted (1822-1903), his sons and firm created designs for over 6,000 landscapes across North America, including many important parks. Lakeshore Highlands, our LHA neighborhood, was designed in 1915 by the Olmsted sons, John C. and F. L. Jr. This remarkable legacy encompasses Oakland’s Mountain View Cemetery, the Biltmore Estate (North Carolina), U.S. Capitol and White House grounds, Mount Royal in Montreal, Boston’s Emerald Necklace, Prospect Park (Brooklyn, NY). Millions of us benefit from their exemplary projects every day. Here in our neighborhood, we have the Olmsted team to thank for our tree-lined, curvaceous, hilly blocks interspersed with open green spaces and strategic view spots.

The Olmsteds believed in the “restorative value of landscape” and were committed “to visually compelling and accessible green space that nurtures the body and spirit of all people, regardless of their economic circumstances.” Whether in Buffalo, Seattle, Los Angeles, Atlanta’s Druid Hills, or Chicago’s Washington Park and Olympic venue, the magnitude of their work and its influence on America’s landscape are astonishing.

Olmsted’s sons were instrumental in the creation of the National Park Service, in the advancement of the role of city planning, and were founding members of the American Society of Landscape Architects.

The National Association for Olmsted Parks (NAOP) “advances Olmsted principles and the legacy of irreplaceable parks and landscapes that revitalize communities and enrich people’s lives,” and are working to document the extensive legacy. NAOP encourages public officials, developers, enthusiasts, and communities to “preserve, restore and promote Olmsted-designed parks and landscapes.” Lakeshore Homes Association participates in NAOP.

LHA was featured in NAOP’s summer newsletter issue. The following is an excerpt:

“Lakeshore Homes Association: Preservation in Oakland, CA

The Lakeshore Homes Association, the second oldest west of the Mississippi, was founded in 1917 by the developer of Lakeshore Highlands as a way of protecting this “residential park” in the City of Oakland, California, designed by the Olmsted Brothers. Covenants, conditions and restrictions that go with the deeds to properties are managed by the Association. An advisory Neighborhood Preservation Committee reviews changes to the exterior of properties…

The Association also acts as a repository of historic plans, photos, and artifacts. It has given photos to the Oakland History Room of the Library. The Association plans events for the community and provides a structure for emergency preparedness using a cluster approach….In the 1950’s, the Association lost a road battle that resulted in the loss of 160 homes. However, it was subsequently able to get the support of the City in concert with Mills College and other neighborhood groups for a ban on large trucks. The truck ban remains in effect and is the only one in the country on an interstate highway (580 Freeway)….”

[All quotes, except the article excerpt, from “Saving America’s Great Historic Landscapes” by NAOP.]